BK101

Knowledge Base

Universal School of Knowledge

These are just some of the ideas of what a Basic Knowledge 101 School of Thought would look like when it becomes a Physical School, and not just a VR school, or an Online School with Professional Tutoring, or an Artificial Intelligent Teaching Avatar that runs on your computer or smartphone, or an Outdoor School or Living Laboratory. The School of Life.

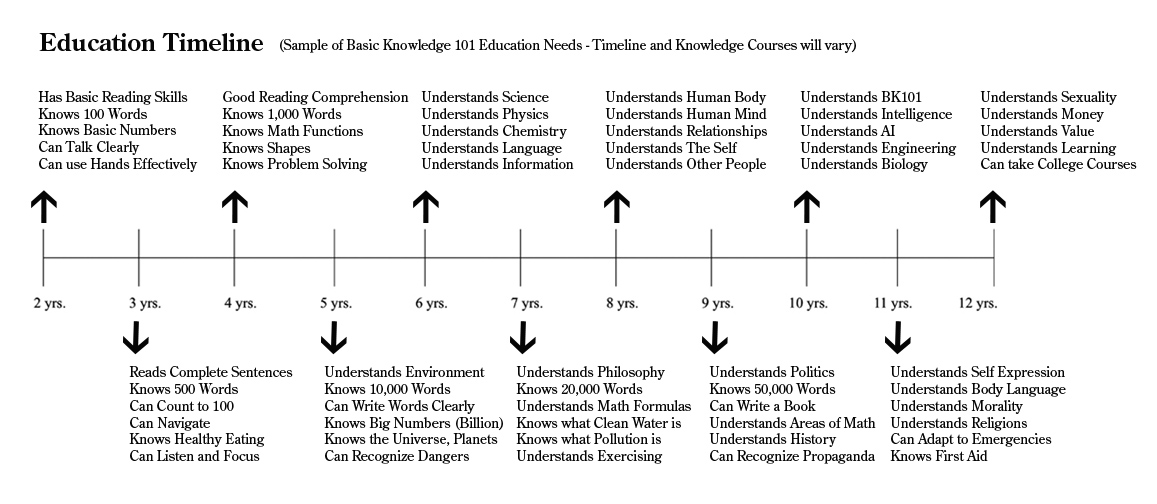

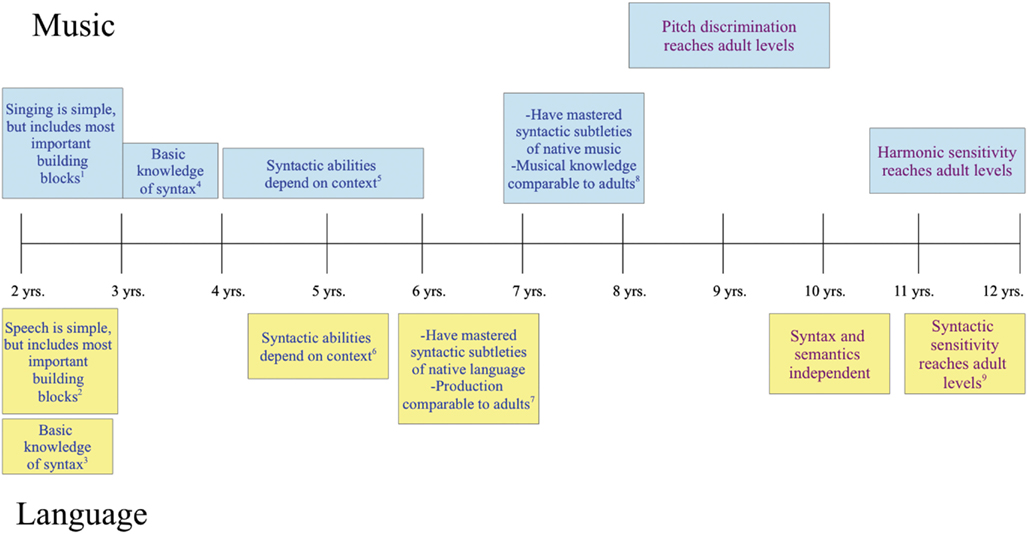

Every student needs to see their education in a comprehensive timeline, and see the stages of learning. This way the student can keep track of where they are and also understand where they need to be. The student should understand the knowledge and information that they have acquired so far, and also understand how much more knowledge and information that they need in order to guarantee that they have enough knowledge and enough skills to pursue any career and pursue any dream that they have. The Education Timeline will work along side Child Development Milestones, Adult Development Milestones and Intelligence Tests. Course Templates are used to define the look and feel of a course. A template determines the layout of the content and interactions between a learner and a course. Summary Outline.

Transcript is a certified record of a student throughout a course of study having full enrollment history including all courses or subjects attempted, grades earned and degrees and awards conferred. Report Card communicates a student's performance academically.

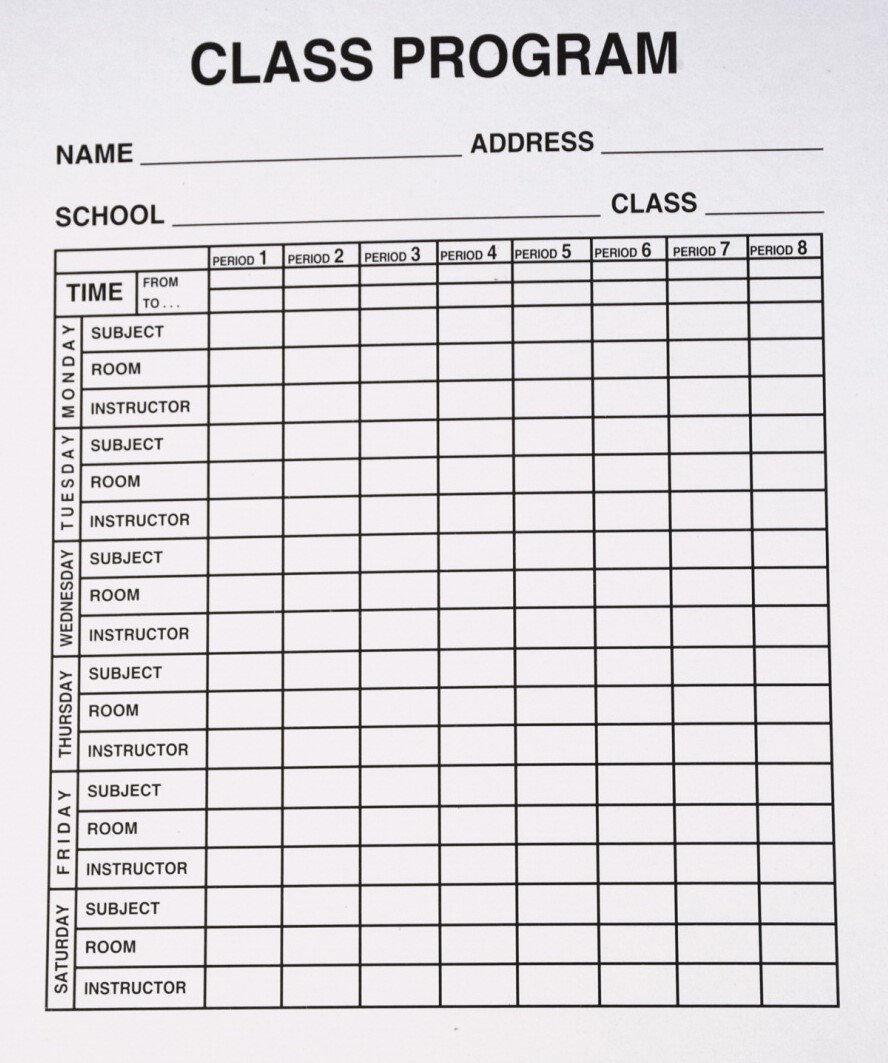

Students must learn to understand how to schedule and organize their learning experience over their first 12 years of learning, or the first 20,000 Hours of Learning. This will help students to see what this first phase of education looks like as a whole. This will help them see what choices they may have, and when and where their options will be in reference to their learning tree or education timeline. They can also plan and predict where their education will take them, so they can plan what career is best for them, and know what actions to take that would be best for themselves and the world around them.

The starting point will depend on a students age and their level of knowledge and skills. Learning the right things at the right time makes learning easier. Learning things in the right order will help understand the knowledge. So if you skip parts, or jump ahead, or cheat, you may minimize your ability to use this knowledge to its full potential.

This is just a First Draft, so it will be modified and expanded as time goes on. (9/2018). Subject Sitemap.

Lessons Outline - Lesson Design - Lesson Development

Communication

Learning how to Talk Effectively. Learning how to Listen Effectively. Learning how to Read Effectively. Learning how to Write Effectively. Learning how to Transfer and Receive information Effectively. Learning how to Process Information Effectively.

Information Literacy

Learning how to understand information Effectively. Learning how to understand different types of information. Understanding Word and Symbol Meanings. Understanding Language. Understanding Body Language and Environmental Language.

Learning and Teaching

Understanding learning methods and teaching methods. Learning how to teach yourself. Learning how to teach others. Understanding the purpose of education. Understanding Knowledge.

Human Body and Mind

Understanding Human development and Human Intelligence. Understanding the responsibilities of maintaining a healthy mind and body. Understanding the importance of Clean Water and Healthy Foods. Understanding dosage and consuming in the correct amounts.

Problem Solving

Learning how to solve problems. Learning how to come up with ideas. Learning how to create new things. Understanding Math, Science, Engineering, Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Environment, Energy, Shelter and so on.

Seeing Your Future

If students could see where education is taking them and how the knowledge they're learning will benefit them, then students will educate themselves for the rest of their lives. 99% of all the things that you can learn will bring you pleasure. So learning should be addictive because learning is its own reward, the incentive to learn is there, you just have to learn that first. If you don't feel the pleasure of learning, then there are a few reasons why that you must understand every time you begin to learn something or read something. Are you learning something important? Are you learning something at the right time? So if you feel that the information is not important then you will not find pleasure when learning something new. And if you are learning something at the wrong time where you cannot understand what you are learning then you will also not feel good about what you are learning or will you know how to accurately process this new information in order to effectively use this information and knowledge in the future.

Mission: To make every student a self directed learner who is not dependent on classrooms or schools to learn what is needed. Foster the responsibilities and the skills of learning, so that every student fully understands what learning is, and is not.

Main Goals: Make sure that every Student has Access to the Worlds Most Valuable Knowledge and Information. And then teach every student how to use knowledge and information Effectively and Efficiently as possible. And then make sure that every student knows all the different ways there are to learn and has all the necessary tools and technology that are needed for learning. And then get out of the way, because our students have a life to live, and they also have a lot of problems to solve that they have inherited from an ignorant society. We owe this to our children, we owe this to ourselves, we owe this to our students, and we owe this to the hundreds of millions of future generations.

Every Student should be given the ability to know anything that one chooses to know and can be known, and the capacity to know everything that there is to know. This is not to say that students will spend every day of their life learning, it is saying that learning will happen more often because each student will understand what learning is, and, how to recognize learning moments when they happen. Students lives will be balanced and rich with experiences, but they will also be intelligent, because they will be learning the right things at the right time, and have access of the most valuable reading material that this world has to offer. Each student will understand Cumulative Learning, and how Cognitive Architecture is built.

To Know Everything, To Become Intelligent, To Solve Every Problem, To Live Well, To Love.

Everything There Is To Know About Everything There Is. Will Humans ever be able to know everything in the Universe?

The only time that you can accurately understand something is when you have the necessary knowledge and information that's needed in order to understand it. There are things that you cannot see or understand unless you are trained to see and have learned how to see what you could not see before. To you, something's do not exist until you have the necessary knowledge and information that's needed in order to realize the existence of something. Example: Let's say you were drinking water from a fountain, but the water is polluted, so you got sick. But what you did not know is that there was another water fountain down the road that had clean water. So if you were informed and knew about the clean water fountain, you could have drank water from that clean fountain instead of drinking dirty water that made you sick. And one more thing, lets say you had no idea that the water that you were drinking was the cause of your sickness? So until you learn that the water is the cause of your sickness, you will continue to be sick. That's how most everything in life works. Learning is your power. Never underestimate the importance of learning. But you must learn the right things at the right time.

First you have to know, then you can understand, then you can be aware it, then you can figure out how to be in control of the input and output, or the cause and effect.

So what do you need to know? What would be the perfect education? What would be the most valuable knowledge and information that a person could have? What would be the most valuable skills that a person could have? What is valuable? Valuable is something that has been calculated and measured as being the most important for life, prosperity and happiness.

What would be the most important questions that everyone should have the answers to? What is happiness? What is sadness? What does success mean? What is confidence? What is love? What is fear? and so on...

As we teach each student how to improve their life and improve their world, we will also teach students how to read, how to write, how to use math, how to use science, how to communicate, teach them problem solving, and also teach them how to be an engineer, all at the same time. So as each student learns how to improve their world, they will also learn valuable skills and knowledge at the same time. Counting the Things that Matter.

Simultaneous Subject Teaching Creating Associations and Connecting Knowledge with things you do in Life everyday.

Timeline is a way of displaying a list of events in chronological order, sometimes described as a project artifact. It is typically a graphic design showing a long bar labeled with dates alongside itself and usually events labeled on points where they would have happened.

Timeline would show the 5 Core Subjects and Testing needed at each step, which would vary depending on the abilities of each student. Would not be limited by age or grade, mostly just ability.

This school is not about memorizing boring details, this is about effective learning, and maximizing the students time at school, so that every student receives the best education possible. And that every student is more intelligent then the previous generation, and that each student will grow up to be free thinkers and not a robot to be manipulated by other peoples ignorance. I don't know about you, but I'm looking forward to intelligent people solving all our problems, the future is going to be freaking awesome!

Testing is only used as a guide to help you measure the level of intelligence that you have acquired at a particular moment in time. Testing is also used as a guide to help you plan your education needs. No more grades, just levels of intelligence.

Some more ideas about Testing.

No one will ever say that I have to pass this test. Instead each student will be saying, "My examinations are going well, but I still need to learn more". There will be no falling behind, just behind on schedule, which is based on the average time it takes for a student to acquire a particular level of intelligence. You will get there, and when you do, the rest is up to you. Learn as much as you can, but remember, your school will always be here for you, you are a member of this school for life. There will be no bogus graduations or lame commencement speeches, there will be only levels of intelligence that you have obtained, and earned. And since this school is always progressing and improving, then coming back to school from time to time will definitely be a benefit to you.

Every kid who leaves school each day should be saying, "I'm so freaking glad that I went to school today", every student should be saying that every day, if not, then the school they are attending is ineffective. I went to that school, and it sucked. There is nothing more exhilarating then learning, so if you don't feel good when learning, then your teacher is not teaching right, or not teaching the subject correctly for your particular style of learning. Going to school should be an incredible opportunity. Everyday that you have a chance to go to school should be thought of as a chance to learn something important. You should be saying, "I have to go to school today because I have to figure out this problem that I'm having in my life", or, "I got to go to school today because I have some important questions that need answering." Every kid coming to school should feel like they are coming home, like they are coming to a place of sanctuary. A place of enlightenment. This is what every school should be, if not, then the school is ineffective.

Students will be more intelligent then their parents. Reason 1: Students will be learning more then their parents. Reason 2: Most parents have stopped learning, so parents will not be up to date on what is known. So every student will be responsible for teaching others, making sure that everyone is aware of valuable knowledge and information and all the benefits that come from knowing.

Every teacher in the school will be constantly updated on what classes each student has attended, when they attended the class, and if they were tested. Every month each student will be evaluated so they can clearly understand their progress. So if any student needs extra help or needs to catch up in a certain area of knowledge then they will given a chance to do so in each class or be given a private tutor to help them achieve their goals. So there should always be more then one teacher in each class.

Entering a Physical School

Student enters school, teachers find out what the student needs, and then provides these needs to the student. A student will walk into his or her school and either say I'm good, I'm doing a regular schedule today, See you after school, or they will say, I'm not doing a regular scheduled school day, instead I'm working on some personalized needs today.

We want school to be a place where making mistakes is not used a reason to punish you or as a reason to hold you back. So wrong answers will never slow you down or be the end of the world in this school, just as long as you know that having the wrong answers in life can be very dangerous. It's our job to educate you for the real world. We would rather see you make mistakes in school then for you to make mistakes outside school or make mistakes in your life. That would mean we have failed you, and your failure would be our failure. This is why we will do everything possible to make sure that you are successful in what ever you choose to be or what ever you choose to do in life, that is our goal.

School is supposed to be a place where you learn about the human experience and human development, and also learn about the world we live in and the universe that surrounds us.

Schools need to have regular scheduled classes, because you can maximize resources and peoples time by bringing many people together to collaborate and cooperate to make the classroom experience as effective and efficient as possible, like when hundreds of people get together to make a movie, you could never make a movie if people were on flex time and on their own schedule. And if a school is not utilizing time people and resources effectively and efficiently, then that school would be ineffective in teaching and learning, like most every school in the world is now. The Power of Language needs to be fully understood.

School Counselor for every student

This is not saying that education should be unstructured, we need an education timeline and structure, but we also need to be Spontaneous and Flexible, and create a one to one teaching and learning experience for every student, one that is customized personally for each persons needs.

Development - Routines - Collaborative Education

School of Thought is a collection or group of people who share common characteristics of opinion or outlook of a philosophy, discipline, belief, social movement, economics, cultural movement, or art movement. Schools are often characterized by their currency, and thus classified into "new" and "old" schools. There is a convention, in political and philosophical fields of thought, to have "modern", and "classical" schools of thought or intellectual tradition. Hundred Schools of Thought.

Update definition of School of Thought is a school who's main purpose is to disseminate the most valuable knowledge and information that the world has to offer. Knowledge that has been created collectively up to the present moment. The goal of Knowledge is to foster Intelligence and create unlimited potential in every student.

Paradigm in science and philosophy, is a distinct set of concepts or thought patterns, including theories, research methods, postulates, and standards for what constitutes legitimate contributions to a field.

Paradigm Shift is a fundamental change in approach or underlying assumptions, a scientific revolution. A fundamental change in the basic concepts and experimental practices of a scientific discipline. Enlightenment.

A student doesn't need to know everything, they just need to know where everything is, in case they need it. Working Memory.

Constructivism (psychological school) refers to many schools of thought that, though extraordinarily different in their techniques (applied in fields such as education and psychotherapy), are all connected by a common critique of previous standard approaches, and by shared assumptions about the active constructive nature of human knowledge. In particular, the critique is aimed at the "associationist" postulate of empiricism, "by which the mind is conceived as a passive system that gathers its contents from its environment and, through the act of knowing, produces a copy of the order of reality."

5 Classes - 1 hour Each

With 10 minutes of Questions - 5 Minutes of Relaxation - 15 minutes between each Class - Flextime

Communication - Information Literacy - Problem Solving - Human Development - Learning - Teaching

Feedback At the end of each class there will be 10 minutes of questions from students. All questions will posted until all questions are answered. Questions will appear on the Blackboard or other media platforms that can display public organized knowledge (websites, information stations, library and so on) Then if needed, questions and answers will be indexed and categorized in the proper locations in the Public Knowledge Database. Flexibility will always be considered depending on the students needs

Collaborative Classroom - Class Dojo - Social Learning

The last 5 minutes of every class will be for processing, meditating, stretching, tai chi, or other forms of quite refection and thinking.

All classes will be video taped for future reference, and to improve teaching methods, and to allow students who miss class to review what they have missed.

15 minutes between each Class. (Socialize, Study, Eat, Drink, Stretch, Make Phone Calls, Seek Counseling and so on)

Food will be available throughout the entire school day.

The cafeteria will also double as a nutrition class and food awareness zone.

Students and Teachers will learn where their food comes from as well as all the ingredients and nutritional values.

Students and Teachers can also monitor their Weight, Height, Blood Pressure and Calorie Intake.

(Urinalysis and Blood Work can be done at the Nurses Office when needed)

Typical Schedule (Time Flexibility and Options Available)

8:00 - 9:00 AM |

9:15 - 10:15 | 10:30 - 11:30 AM

1.5 Hours for Lunch: Eat and

Drink - Meditation - Yoga - Walk -

Exercise -

Study - Processing

1:00 PM - 2:00

| 2:15 - 3:15 PM

End of the Day

Healthy Snack - Research

- Activities -

Meditation - Awareness - Counseling -

Tutoring - Calendar - Planning

In reality,

schools should be open every day 24/7 to accommodate all

schedules. Teachers and

counselors should work in shifts and be in school 24/7. Just like a

Hospital has Doctors available 24/7, schools should also have education

available 24/7. The world is in an emergency situation right now. That's

because our current education system is extremely ill and highly

contagious. Schools need to be cured so that schools can start healing

minds instead of infecting minds with irrelevant information. BK101's

first physical school will be open 27/7. And BK101 will also be the most

advanced school on the planet, only because it needs to be.

This is what School will be...

What ever you feel like learning today,

we will help you learn. As long as you keep in mind that there

is valuable knowledge and information that you need to learn.

Knowledge that will give you more abilities, more control, more

power, more freedom, more potential, more possibilities, and

also increase your chances significantly of having a more

prosperous and fulfilling life. So what ever you feel like

learning, you should be able to incorporate valuable knowledge

lessons into that particular learning experience that you chose.

So if you wanted to climb a mountain, you should use climbing a

mountain is a great opportunity to learn. You could learn a lot

about the environment, and also learn a lot about the physical

and mental capabilities of the human body and the human mind.

What ever you feel like learning today,

we will help you learn. As long as you keep in mind that there

is valuable knowledge and information that you need to learn.

Knowledge that will give you more abilities, more control, more

power, more freedom, more potential, more possibilities, and

also increase your chances significantly of having a more

prosperous and fulfilling life. So what ever you feel like

learning, you should be able to incorporate valuable knowledge

lessons into that particular learning experience that you chose.

So if you wanted to climb a mountain, you should use climbing a

mountain is a great opportunity to learn. You could learn a lot

about the environment, and also learn a lot about the physical

and mental capabilities of the human body and the human mind.

Schools will work on real problems that

are plaguing the world. Students will learn what knowledge,

information and skills are needed to solve these problems. So

the

incentive and reasons to learn will always be present.

The first 16 years of your life is the best time to learn,

especially if you learn the right things at the right time,

because that knowledge will benefit you forever. But if your

education starts out slow or late, or if your education was

never adequate to begin with, then you will need to repair old

knowledge as well as learn new knowledge, so learning will take

longer, and learning will be a little more difficult, but

learning will still be totally worth it and incredibly

rewarding, because you will be able to relieve yourself of

ignorance that was doing you more harm then good. And this

realization will inspire you to keep learning. And

Epiphanies

will

continually happen to you, as long as you keep learning the

right things at the right time.

Self-Directed -

Inspired -

Ideas

The constructs of language helps us acquire knowledge and store

knowledge more efficiently and more effectively, And that is a

proven fact. Take away language, or reduce language abilities,

you will reduce learning, and you will reduce awareness, and you

will reduce understanding. And that is one of the main reasons

why so many schools are so ineffective, because literacy and

comprehension abilities are extremely inadequate.

When students are learning how to read, they should be reading

about the most valuable knowledge and information that is

currently available, and also be learning about why certain

knowledge and information is valuable, so that every student

will eventually have the ability to learn on their own, and be

able to seek out valuable knowledge and information in all its forms.

Flex Time - Sleeping Schedules

No Strict or Stubborn Schedules, everyone needs Flexibility. You just can't have these strict and stubborn scheduled Dictations, that thing schools call a Classroom. Coming to class should never be a requirement. The only requirement there should be is that a person learns. Students should not be forced to learn at a particular time or place, or forced to learn by dictation, or forced to learn by scheduled testing. Ask the student what they wish to learn? What's important to them? As long as they understand knowledge and skill requirements, and understand the benefits of those requirements, students should be given the freedom and the resources to learn what ever they need to learn. You should never limit the ways that a student can learn. Putting strict requirements on learning restricts learning.

Shifting school start times could contribute $83 billion to US economy within a decade

Teens get more sleep with later school start time showed improved attendance and grades.

Flextime is a flexible hours schedule that allows workers to alter workday start and finish times. A system of working a set number of hours with the starting and finishing times chosen within agreed limits by the employee.

Flexible is capable of being changed and able to adjust readily to different conditions. An opportunity to be spontaneous. Willing to make concessions or compromises. Able to bend easily.

Time Discipline (PDF) - Remote Work (telecommuting) - Temp Work

School Start Times for Middle School and High School Students — United States, 2011–12 School Year (Research by CDC)

Poor grades tied to class times that don't match our biological clocks. Schedules of night owls, morning larks and daytime finches may predict their educational outcomes.

Electives - Time Management - Sleeping - Nocturnal (shift work)

You don't want to force people to learn something when they are not ready to learn, or force people to learn something that they don't need to learn at a particular time in their studies. We don't want people to be totally subjected to schedules, we sometimes have to change schedules to meet the particular needs of each person.

Routines are necessary, but not always.

You don't need to force students to show up to school in order to learn, students should have the option to learn at home, or in other groups in other places. The school in just a Headquarters. So you can just check in with your nearest BK101 Headquarters to let us know how you're doing. If we don't hear from you, we may call you or have one of your friends check in with you to make sure that everything is going fine. We might one day even pay you to go come to school, you can call it an investment in your future, or just think of it as just one of the many incentives for coming to school.

You don't want people to learn things that they can't handle emotionally or intellectually. And you don't want people to learn things that they don't fully understand, because then they will not learn effectively, and they will also waste time and energy. So the sequence is important, just like the sequence of a developing human, there is a logical order to development.

Team Sports are great, but you should also have a sport that you can practice all own your own. Then you can test your abilities anytime, and you don't have to wait for others. Why isn't learning a sport? It's one of the most important skills a person can have. You can compete with others, or you can compete with yourself.

Student says "I want to learn this?" Teacher then explains what things are needed first to accomplish their goal, and then provides the needed knowledge, information and courses for the student, so that they can reach their desired goal. Just as long as the goal is a benefit to them and to others, and not a distraction, or an incorrect path to take, if so they must do it on their own time.

Everyone should be free to explore, and they should be given the best knowledge and information that is available that would help them on their journey of exploration.

School should start early and end late to accommodate students schedules. Students who sleep late, go home late. Students who start early, go home early. But the most important thing is to teach students about the importance of Good Sleep Habits, and the importance of Time Management, the benefits of having a Schedule, the importance of Punctuality, and the importance of Prioritizing. You do not want to encourage staying up late, or getting up late, but you don't want to restrict sleeping habits, or punish different sleeping habits either. We must teach students about good sleeping habits and the benefits of having a regular schedules, as well as, know how to survive if sleeping schedules change. Enforcing earlier bedtimes is totally ridiculous. It's better to teach students how to maximize their waking hours, and how not to waste too much time when they're awake.

Respecting other Peoples Time

Punctuality is the characteristic of being able to complete a required task or fulfill an obligation before or at a previously designated time. "Punctual" is often used synonymously with "on time". It is a common misconception that punctual can also, when talking about grammar, mean "to be accurate". According to each culture, there is often an understanding about what is considered an acceptable degree of punctuality. Usually, a small amount of lateness is acceptable; this is commonly about ten or fifteen minutes in Western cultures, but this is not the case in such instances as doctor's appointments or school lessons. In some cultures, such as Japanese society, and settings, such as military ones, expectations may be much stricter. Some cultures have an unspoken understanding that actual deadlines are different from stated deadlines, for example with Africa time. For example, it may be understood in a particular culture that people will turn up an hour later than advertised. In this case, since everyone understands that a 9 pm party will actually start at around 10 pm, no-one is inconvenienced when everyone arrives at 10 pm. In cultures which value punctuality, being late is seen as disrespectful of others' time and may be considered insulting. In such cases, punctuality may be enforced by social penalties, for example by excluding low-status latecomers from meetings entirely. Such considerations can lead on to considering the value of punctuality in econometrics and to considering the effects of non-punctuality on others in Queueing Theory (PDF).

Staying on Time Tips

Have everything ready the night before.

Keep your essentials near the door.

Create a staging area near the door.

Anticipate delays before they happen.

Commit yourself to being 15 minutes early for everything.

Overestimate the time it'll take to get there.

Don't hit the snooze button.

Re-examine how long your daily tasks really take.

Time yourself a few days in a row to see how long it actual.

ttakes you to perform certain tasks.

Wikihow: Be Punctual

A slow learning process has many benefits. Taking your time learning something, or learning slowly and methodically, can make learning more effective. Though learning fast can be more efficient, learning fast is never more effective than slowly learning. But each process needs to be done correctly in order for learning to be effective. Slow learning can utilize the power of the spacing effect and improve long-term memory performance, but only if learning is not too slow, because people might not remember what was learned in the last lesson. So slow or fast will always be relative to the learners skill and needs, as well as the time that is allowed to learn something. Full immersion into a subject might be fast, but only the resources are available. Either way, if you have enough time, you still have to use time wisely.

Holodeck Learning Immersion - Simultaneous Subject Teaching

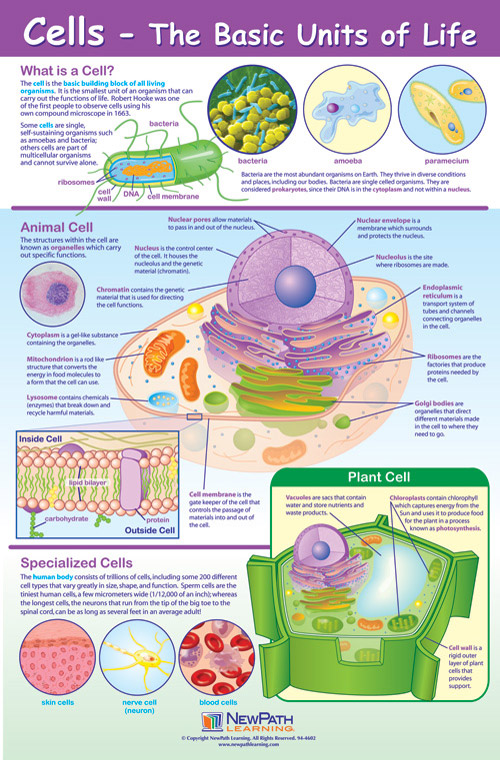

Classroom of the future will be like Holodeck from Star Trek and the Loading Program from the Matrix. If you don't have four empty walls then you can have three totally white walls to project images on and play sound from, with the windows of the room at your back. Total submersion into a subject, interactive and adjustable, making learning an incredible and enjoyable journey. The room would also have a digital display that would show temperature, oxygen level, humidity and other environmental factors to guarantee that the student has a comfortable learning environment. You can also do this using big learning posters and info-graphs that cover the walls. They can even design and print their own posters as they learn more about the subject and how the information in each subject should be presented so that understanding is maximized.

Exocentric Environment refers to a virtual reality or some other immersive environment which completely encompasses the user, e.g. by placing the viewer in a room made up entirely of rear projection screens. Systems which merely display a virtual reality directly to the user (e.g. using a head-mounted display) do not qualify. They are endocentric environments.

Holography

Immersion (virtual reality) is a perception of being physically present in a non-physical world. The perception is created by surrounding the user of the VR system in images, sound or other stimuli that provide an engrossing total environment.

Virtual Reality

Holodeck is a fictional plot device from the television series Star Trek. It is presented as a staging environment in which participants may engage with different virtual reality environments. From a storytelling point of view, it permits the introduction of a greater variety of locations and characters than might otherwise be possible, and is often used as a way to pose philosophical questions.

Nvidia Holodeck

Mixed Reality - THEORIZ - RnD test 002 (vimeo) White Room using in house tracking system (Augmenta) and Vive VR tracking technologies with real time video and projection mapping in space.

Scientific Modeling is a scientific activity, the aim of which is to make a particular part or feature of the world easier to understand, define, quantify, visualize, or simulate by referencing it to existing and usually commonly accepted knowledge. It requires selecting and identifying relevant aspects of a situation in the real world and then using different types of models for different aims, such as conceptual models to better understand, operational models to operationalize, mathematical models to quantify, and graphical models to visualize the subject. Modelling is an essential and inseparable part of scientific activity, and many scientific disciplines have their own ideas about specific types of modelling.

Immersion using Simultaneous Subject Teaching

Immersion Poster Samples

Cells - Building Blocks of Life

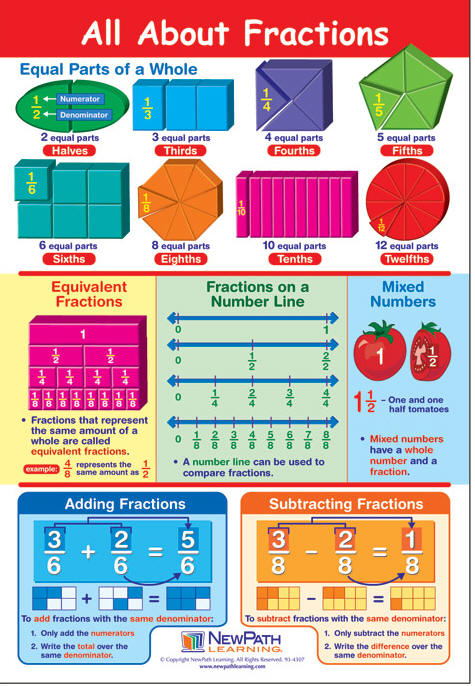

Math

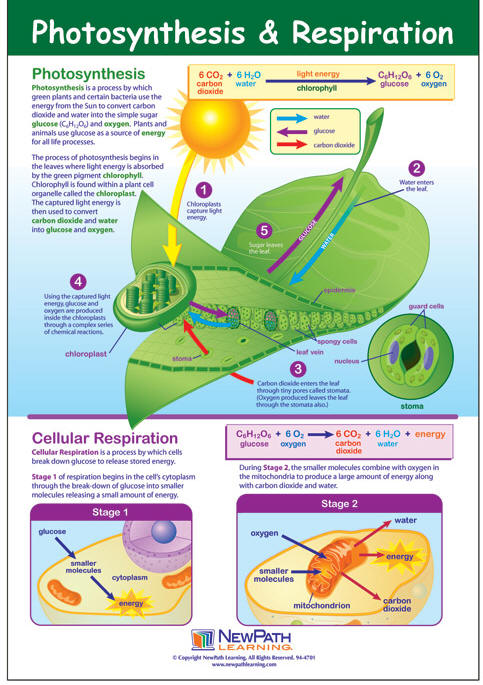

Photosynthesis (solar power) - Energy

Day Dream Education educational posters and interactive software with over 2,000 innovative and engaging educational products.

Outdoor School Programs

Learning Outside the Classroom - The Classroom has always been Outside

Not all schools days will be inside in the classroom. One day a week schools must take classrooms outside and have students and teachers venture into the community, into businesses, into local government, and into the environment. Students must see our problems first hand and talk to the people who are most affected. Students should fully understand most of the social issues they will face as they get older. People must be prepared for the future because that is where they are going. And we can even make games of some of our learning experiences, because learning is fun.

Farms to School Food Education Program - Simultaneous Subject Teaching

Learning Space refers to a physical setting for a learning environment, a place in which teaching and learning occur. The term is commonly used as a more definitive alternative to "classroom," but it may also refer to an indoor or outdoor location, either actual or virtual. Learning Spaces are highly diverse in use, learning styles, configuration, location, and educational institution. They support a variety of pedagogies, including quiet study, passive or active learning, kinesthetic or physical learning, vocational learning, experiential learning, and others.

Outdoor instruction makes students more open to learning. Being taught science subjects outdoors increases student motivation.

Learning through play, children can develop social and cognitive skills, mature emotionally, and gain the self-confidence required to engage in new experiences and environments. Key ways that young children learn include Playing, being with other people, being active, exploring and new experiences, talking to themselves, communication with others, meeting physical and mental challenges, being shown how to do new things, practicing and repeating skills and having fun. Play develops children's content knowledge and provides children the opportunity to develop social skills, competences and disposition to learn. Play-based learning where the teacher pays attention on specific elements of the play activity and provides encouragement and feedback on children's learning. When children engage in real-life and imaginary activities, play can be challenging in children's thinking. To extend the learning process, sensitive intervention can be provided with adult support when necessary during play-based learning.

Exercise and physical activities have many benefits on the mind and the body, but you still need lots of knowledge in order to fully utilize all those benefits. Learning is the single greatest exercise that most people overlook.

Playground Zoning increases Physical Activity during Recess. Zones with specific games can improve physical activity, improving a child’s chance of engaging in the recommended 60 minutes of “play per day. vimeo

Use a Playground as a way to teach Science, Math, Physics, Human Development, Body Smart, Environment, Sports, Social Interactions and teamwork, to name a few.

Field Research is the collection of information outside a laboratory, library or workplace setting. The approaches and methods used in field research vary across disciplines. For example, biologists who conduct field research may simply observe animals interacting with their environments, whereas social scientists conducting field research may interview or observe people in their natural environments to learn their languages, folklore, and social structures. Field research involves a range of well-defined, although variable, methods: informal interviews, direct observation, participation in the life of the group, collective discussions, analyses of personal documents produced within the group, self-analysis, results from activities undertaken off- or on-line, and life-histories. Although the method generally is characterized as qualitative research, it may (and often does) include quantitative dimensions.

Experience Learning

Field Trip is a journey by a group of people to a place away from their normal environment. The purpose of the trip is usually observation for education, non-experimental research or to provide students with experiences outside their everyday activities, such as going camping with teachers and their classmates. The aim of this research is to observe the subject in its natural state and possibly collect samples. Field trips are also used to produce civilized young men and women who appreciate culture and the arts. It is seen that more-advantaged children may have already experienced cultural institutions outside of school, and field trips provide a common ground with more-advantaged and less-advantaged children to have some of the same cultural experiences in the arts.

Service Learning and Community Engagement

Study Abroad

Outdoor Classroom Project

Nature Play

Taking the Classroom Outside Action Plan (PDF)

Learning Games - Creativity

Takaharu Tezuka: The Best Kindergarten School you've ever seen (video)

Teaching Outside the Classroom

We need to design Jungle Gyms that teach and Playgrounds that Educate.

Body Intelligence - Physical Education

Use big brother and big sister so each kid has an older person to mentor them during their outdoor learning adventure. The outdoor experience must be combined with other skills like math, science, physics, biology, sociology and so on.

Outdoor Education

Advanced Outdoor Courses

Outdoor Schools

Adventurer Schools

Survival Books and Info

Foraging Wild Foods

Nature Benefits

Outdoor Gear Check List and Camping List

Recommended Gear

Backpacking Tips

Schools Out Film

Having children learning outside in nature is extremely important. While they are exploring and discovering you can teach them about the environment at the same time. You can teach them about cause and effect, and how things change for a reason. You can teach them about how some actions cause damage, while other actions minimize impact. Let them know that almost everything in their environment can be explained. So there is a lot to learn, especially about all the benefits of plants, animals and insects. And there is a lot to learn about all the dangers of plants, animals and insects. Related subjects are chemistry, biology, botany, science, physics, math, history, and so on. You can also teach them about how there are things in our world that we can not see with our eyes. But the more we learn, the more we can see, and understand. The outdoors can provide us with a lifetime of happiness, but only if we respect the land. And the only way to create respect, is to learn everything that you can about the earth. Respect comes from knowing , and knowing comes from learning, and learning comes from exploring. Whether the exploring is in the from of reading, researching, or from directly studying the environment, there are always opportunities to learn. Remind children that Life is the Outdoors. And that the Indoor life is not the same thing. Children should understand the differences between the outside world, and the inside world. Both need careful consideration equally, for they both have benefits, and dangers.

Park RX. Stay Healthy in Nature Everyday Program (SHINE)

Fiddleheads Forest School

Chippewa Nature Center

All Friends Nature School

The Brooklyn New School

The Natural Start Alliance

Outdoor Preschools in greater Seattle

Shaker Lakes

Being outside is so important to health that Doctors are writing Prescriptions for Outside Time. The prescriptions tell Patients to go outside and spend time in Nature at least once a day. Being outdoors in Natural Spaces and Parks is healthy or you physically and mentally.

The Nature Cure. Inside the health Revolution that could change your life.

Consideration is the process of giving careful thought to something. Showing concern for the rights and feelings of others. Information that should be kept in mind when making a decision. Kind and considerate regard for others. A considerate and thoughtful act. Morals

Thoughtful is having intellectual depth. Exhibiting or characterized by careful thought. Acting with or showing thought and good sense. Intelligence

Enriching the Outdoor Play Experience

Abstract:

Playgrounds have been ignored as venues for learning, although educational experts have emphasized play as an important aspect in developmentally appropriate programs. Aside from the physical and motor development offered by outdoor play, opportunities to improve social interaction through both social and intellectual play are also available. Early childhood educators should avail of the potential diversity and richness offered by outdoor play environments that you can learn from, simultaneously.

Subject:

Play (Social aspects)

Early childhood education (Methods)

Playgrounds (Social aspects)

Author: Hennger, Michael L.

Pub Date: 12/22/1993

Publication: Name: Childhood Education Publisher: Association for Childhood Education International Audience: Academic; Professional Format: Magazine/Journal Subject: Education; Family and marriage Copyright: COPYRIGHT 1993 Association for Childhood Education International ISSN: 0009-4056

Issue: Date: Winter, 1993 Source Volume: v70 Source Issue: n2

Accession Number:14982895

Full Text:

Teachers, administrators and others generally consider playgrounds and the activities that occur there less important than indoor spaces in the lives of young children. This view is reflected in textbooks used to prepare teachers for early childhood education (e.g., Brewer, 1992; Feeney, Christensen & Moravcik, 1991; Lay-Dopyera & Dopyera, 1990; Seefeldt & Barbour, 1990). In a quick review of these texts, the author found an average of 21 pages describing the indoor play setting and its preparation and only a little under 5 pages discussing the outdoor play site. Similarly, although the National Association for the Education of Young Children emphasizes play as an essential ingredient in developmentally appropriate programs, it gives few specifics for providing such experiences outdoors (Bredekamp, 1987).

From their inception, playgrounds and outdoor play experiences have been viewed primarily as an opportunity to develop physical skills through vigorous exercise and play (Frost & Wortham, 1988). Despite this long-held attitude, educators are becoming more aware that outdoor play can be much more valuable than previously assumed.

Clearly, outdoor play can stimulate physical-motor development (Myers, 1985; Pellegrini, 1991). In addition, however, playgrounds are a positive setting for enhancing social interaction (Kraft, 1989; Pellegrini & Perlmutter, 1988). Further evidence indicates that well-equipped playgrounds can stimulate a variety of play types, including dramatic play (Henniger, 1985).

Outdoor play can be as effective as indoor play in facilitating young children's development. Frost & Wortham (1988) suggest "The outdoor play environment should enhance every aspect of child development--motor, cognitive, social, emotional--and their correlates--creativity, problem-solving, and just plain fun".

With a little effort, playgrounds can move from their current rather sterile status (Frost, Bowers & Wortham, 1990) to more stimulating, creative spaces for young children. Most playgrounds would benefit by more variety in available materials and spaces. Movable toys and equipment can make playgrounds into spaces where children can have a greater effect on their environment. In addition, concerned adults need to ensure that children have numerous opportunities for dramatic play outdoors. Finally, Playgrounds need to be safe environments where children are free to explore without fear of injury from materials or equipment.

The play experiences of young children are often categorized either according to the level of intellectual functioning or in relationship to their social complexity. Smilansky (1968) defined four major types of cognitive or intellectual play (functional, construction, dramatic, games with rules) and Parten (1932) suggested four additional social play categories (solitary, parallel, associative, cooperative).

To help facilitate these important play types in the indoor setting, early educators have consistently provided children with a large variety of quality play materials and toys (e.g., blocks, manipulatives, art materials, housekeeping items, dramatic play materials, musical instruments and objects from the natural environment). Teachers spend considerable planning time organizing these materials into interesting and inviting centers and ensuring that new choices are available to children on a regular basis.

Options for the playground are much more limited (Frost, Bowers & Wortham, 1990). Although swings, slides, climbers, tricycles and a sandbox are common, this equipment is not sufficient to stimulate a broad spectrum of quality outdoor play. Spaces for children to engage in solitary play (e.g., a cluster of plants with a small opening for the child), toys and props for dramatic play (see Jelks & Dukes, 1985) and materials for construction play (e.g., outdoor blocks, wooden boards and boxes, small cable spools, gardening space and tools, old tires) are needed to enrich the variety and complexity of the playground. Concerned teachers should periodically reorganize the playground to provide new and exciting choices for young children.

Esbensen (1987) suggested that teachers consider the outdoor setting to be an extension of the classroom, with the same potential for enhancing development. He defined seven play zones that should exist on every playground: transition, manipulative/creative, projective/fantasy, focal/social, social/dramatic, physical and natural element. Esbensen recommended the addition of a playhouse containing a table and chair set, housekeeping toys and equipment, and other home-related accessories to stimulate more social/dramatic play outdoors. With additional planning and preparation, teachers can create these zones and ensure that the children participate in a variety of play types.

Movable Toys and Equipment

An essential element of learning in the early childhood years is the opportunity to affect the environment. Children learn a great deal by manipulating the materials and equipment in their world (Kamii & DeVries, 1978). Play helps children actively make sense of their environment (Piaget, 1951). Through active play, children are learning, exploring and creating. Wassermann (1992) called this the generative function of play.

Nearly all of the indoor play materials can be manipulated by children. Puzzles, blocks, art materials, musical instruments and dramatic play props are among the many materials commonly found indoors. On the playground, however, this diversity is rare. Frost, Bowers and Wortham (1990) recently conducted a survey of American preschool playgrounds and found that tricycles were most often available, with an average of about three per playground. Loose tires, sand, wagons, barrels and loose boards (building material, stacking blocks) were available, in descending order, ranging from about two tires per playground to about one barrel or board to every three playgrounds. Children who play outdoors therefore have very few movable equipment options. Adding more movable toys and equipment is not a difficult task. Children do not need expensive or hard-to-find items. In fact, common and inexpensive materials generally suffice. A good example of a creative playground space made with inexpensive materials is the Adventure Playground designed for older children (see Louv, 1978; Michaelis, 1979; Pedersen, 1985). The Adventure Playground, which originated in Denmark in the 1940s (Pedersen, 1985), consists of a rich variety of building materials such as scrap lumber, bricks, tires, rope and sand. With the assistance of a trained play leader, children spend countless hours building, using and tearing down their play structures, and then beginning the process all over again (Louv, 1978).

Similar materials and tools can easily be added to the preschool playground to enhance young children's opportunities to manipulate and construct in the outdoor environment. The number of tires, barrels and loose boards found on some playgrounds (Frost, Bowers & Wortham, 1990) can be increased and child-sized cable spools, outdoor blocks, gardening tools and small wooden or plastic boxes can be added.

To protect this equipment from weather and vandalism, a storage method is needed. Either a storage shed or part of an existing play structure (such as underneath a slide/fort structure) must be designated to house movable materials when not in use. If the storage area is readily accessible to children, with low shelves and baskets or boxes for loose parts, they can assume responsibility for taking out and returning this equipment.

Providing More Opportunities for Dramatic Play

Literature addressing the issue of play (e.g., Erikson, 1977; Piaget, 1951; Singer & Singer, 1990; Smilansky, 1968) clearly indicates that dramatic or imaginative play is of central importance in the young child's development. Dramatic play is key to success in later formal education. The young child who can readily manipulate symbols in dramatic play is much more likely to accept and effectively use the arbitrary symbol systems of mathematics and written language (Dyson, 1990; Nourot & Van Hoorn, 1991; Smilansky & Shefatya, 1990).

Early educators recognize the importance of this play type and provide materials and space indoors for housekeeping, dramatic play and blocks. These centers, when stocked with quality play materials, stimulate a rich assortment of creative dramatic play that frequently spreads into other areas of the classroom. This variety of opportunities for indoor dramatic play helps meet the needs and interests of the greatest number of children. When new materials are rotated in and out of the classroom centers on a regular basis, these interests are maintained over time.

Although dramatic play opportunities do exist outdoors, they are limited and often created spontaneously by the children themselves with the few available materials. Monroe (1985) found that over half of all child care centers studied had no specific equipment for outdoor dramatic play. Frost, Bowers and Wortham (1990) found dramatic play equipment on fewer than one-third of all preschool playgrounds surveyed.

Dramatic play equipment for use outdoors can be readily purchased or scrounged. Also, some materials that are typically found in indoor dramatic play centers can be taken outdoors. For example, a camp can be set up outside with tent, fire pit, sleeping bags, cookstove and cooking utensils. Placed in a box or similar storage container, related props can be taken outside and returned indoors with relative ease (see Jelks & Dukes, 1985).

A steering wheel from a car or truck can be mounted in a wooden box and placed on the playground to stimulate a variety of dramatic play activities. The same wheel, nestled inside an old boat, can encourage nautical themes. When placed in front of a line of wooden boxes, the steering wheel can become the engine car of a train. A playhouse or fort-like structure can be purchased or constructed by parents and community members and used by children in other creative play themes. Early educators can use their imagination to develop a long list of similar materials that stimulate good dramatic play outdoors.

Safety Issues

Exciting outdoor play spaces also need to be safe environments for young children. Unfortunately, teachers and administrators are frequently unaware of the many unnecessary hazards that playgrounds contain. Although safety issues have been identified for nearly 20 years, statistics indicate that a growing number of children continue to be treated in hospital emergency rooms for injuries incurred on the playground (Wallach, 1990).

The most significant problem on playgrounds today is the hardpacked surfaces under and around equipment (Tinsworth & Kramer, 1989). Falling from playground structures onto a hard surface, such as asphalt or packed earth, can cause serious injury. Concerned adults must replace these surfaces with more appropriate materials (such as 12 inches of sand or pea gravel) to reduce this unnecessary hazard (Thompson, 1991).

Other problems associated with playgrounds for young children include: equipment spacing, improper equipment installation, irregular maintenance and inadequate briefing of children on playground use (U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, 1991). Each of these issues must be addressed so that playgrounds can be low-risk places for children to experiment in and explore.

Conclusions

Children deserve the same diversity and richness in their outdoor play environments as they have indoors. Esbensen (1987) and Frost and Wortham (1988) offer many suggestions for those interested in gaining further insights into this topic. By carefully analyzing the playground setting and determining what is missing, concerned adults can provide a greater variety of play materials and more opportunities to manipulate materials and nurture dramatic play. Then, by spending more time planning for and implementing a more complete playground curriculum, teachers and administrators can help children take full advantage of this marvelous, but frequently underdeveloped, part of a complete early childhood program.

References

Bredekamp, S. (Ed.). (1987). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs serving children from birth through age 8. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Brewer, J. (1992). Introduction to early childhood education. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Dyson, A. (1990). Symbol makers, symbol weavers: How children link play, pictures, and print. Young Children, 45(2), 50-57.

Erikson, E. (1977). Toys and reason. New York: Norton.

Esbensen, S. (1987). An outdoor classroom. Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Press.

Feeney, S., Christensen, D., & Moravcik, E. (1991). Who am I in the lives of children? New York: Merrill.

Frost, J. L., Bowers, L., & Wortham, S. (1990). The state of American preschool playgrounds. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 61(8), 18-23.

Frost, J. L., & Wortham, S. (1988). The evolution of American playgrounds. Young Children, 43(5), 19-28.

Henniger, M. L. (1985). Preschool children's play behaviors in an indoor and outdoor environment. In J. L. Frost & S. Sunderlin (Eds.), When children play (pp. 145-149). Wheaton, MD: Association for Childhood Education International.

Jelks, P. A., & Dukes, L. (1985). Promising props for outdoor play. Day Care and Early Education, 13(1), 18-20.

Kamii, C., & DeVries, R. (1978). Physical knowledge in preschool education. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kraft, R. E. (1989). Children at play. Behavior of children at recess. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance, 60(4), 21-24.

Lay-Dopyera, M., and Dopyera, J. (1990). Becoming a teacher of young children. New York: McGraw Hill.

Louv, R. (1978). Loose on the playground. Human Behavior, 7(5), 18-21, 23-25.

Michaelis, B. (1979). Adventure playgrounds: A healthy affirmation of the rights of the child. Journal of Physical Education and Recreation, 50(8), 55-58.

Monroe, M. (1985). An evaluation of day care playgrounds in Texas. In J. L. Frost & S. Sunderlin (Eds.), When children play (pp. 193-199). Wheaton, MD: Association for Childhood Education International.

Myers, G. D. (1985). Motor behavior of kindergartners during physical education and free play. In J. L. Frost & S. Sunderlin (Eds.), When children play (pp. 151-155). Wheaton, MD: Association for Childhood Education International.

Nourot, P. M., & Van Hoorn, J. (1991). Symbolic play in preschool and primary settings. Young Children, 46(6), 40-50.

Parten, M. (1932). Social participation among preschool children. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 27, 243-269.

Pedersen, J. (1985). The adventure playgrounds of Denmark. In J. L. Frost & S. Sunderlin (Eds.), When children play (pp. 201-207). Wheaton, MD: Association for Childhood Education International.

Pellegrini, A. (1991). Outdoor recess: Is it really necessary? Principal, 71(40), 23.

Pellegrini, A., & Perlmutter, J. (1988). Rough-and-tumble play on the elementary school playground. Young Children, 43(2), 14-17.

Piaget, J. (1951). Play, dreams, and imitation in childhood. New York: W. W. Norton.

Seefeldt, C., & Barbour, N. (1990). Early childhood education: An introduction (2nd ed.). New York: Merrill.

Singer, D., & Singer, J. (1990). The house of make-believe: Play and the developing imagination. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Smilansky, S. (1968). The effect of sociodramatic play on disadvantaged preschool children. New York: Wiley.

Smilansky, S., & Shefatya, L. (1990). Facilitating play: A medium for promoting cognitive, socio-emotional and academic development in young children. Gaithersburg, MD: Psychosocial and Educational Publications.

Tinsworth, D. K., & Kramer, J. T. (1989). Playground equipment-related injuries involving falls to the surface. Washington, DC: U.S. Product Safety Commission.

Thompson, D. (1991). Safe playground surfaces: What should be used under playground equipment? Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance, November-December, 74-75.

U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. (1991). Handbook for public playground safety. Washington, DC: Author.

Wallach, F. (1990). Playground safety update. Parks and Recreation, 25(8), 46-50.

Wassermann, S. (1992). Serious play in the classroom. Childhood Education, 68(3), 133-139.

Michael L. Henniger is Associate Professor, Department of Educational Curriculum & Instruction, Woodring College of Education, Western Washington University, Bellingham.

Gale Copyright: Copyright 1993 Gale, Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

How Dramatic Play Can Enhance Learning

By Marie E. Cecchini MS

Dramatic play can be defined as a type of play where children accept and assign roles, and then act them out. It is a time when they break through the walls of reality, pretend to be someone or something different from themselves, and dramatize situations and actions to go along with the roles they have chosen to play. And while this type of play may be viewed as frivolous by some, it remains an integral part of the developmental learning process by allowing children to develop skills in such areas as abstract thinking, literacy, math, and social studies, in a timely, natural manner.

The Proper Environment

In many classrooms the dramatic play area has traditionally been centered in “housekeeping”. However, when we actually watch children play, we see them reinventing scenes that might take place in other areas of life such as gas stations, building sites, department stores, classrooms, or libraries. This should tell us, that in order to derive the full benefit from dramatic play as it relates to learning, early educators should “set the stage” throughout the classroom.

Setting the Stage

Any dramatic play area should be inviting. Presentation alone should inspire creative and imaginative play. This should be an area where the children can immediately take on a role and begin pretending. In establishing these areas, you will want to consider the following.

1. Each area should incorporate a variety of materials that encourage dramatic play, such as hats, masks, clothes, shoes, tools, vehicles, etc. You can include both teacher-made and commercial materials. The types of materials you supply will depend on the “theme” of the area.

2. Part of your materials list for each area should include items that stimulate literacy activities, like reading and writing. Paper, pencils, a chalk board, wipe-off board, address books, and greeting cards are all examples of materials that might be used to promote the development of literacy skills.

3. Materials should be developmentally appropriate and allow for both creativity and flexibility in play. This includes materials that can be used by all children (unisex) and those that may be used in more than one way (a table as a table, or with a blanket over it, as a dog house).

4. The goal of all areas should be to reinforce grade level appropriate physical, cognitive, and social skills.

Finally, try to change the materials (or props, as they are sometimes called) on a regular basis. Different materials on occasion will enhance the area, spark new interest in a much used area, and allow the children to incorporate new experiences in their play.

The Dramatic Play Skill Set

There are basically six skills children work with and develop as they take part in dramatic play experiences.

Role Playing – This is where children mimic behaviors and verbal expressions of someone or something they are pretending to be. At first they will imitate one or two actions, but as time progresses they will be able to expand their roles by creating several actions relevant to the role they are playing.

Use of Materials - Props – By incorporating objects into pretend play, children can extend or elaborate on their play. In the beginning they will mainly rely on realistic materials. From there they will move on to material substitution, such as using a rope to represent a fire hose, and progress to holding in their hands in such as way to indicate that they are holding an actual hose.

Pretending - Make-Believe – All dramatic play is make-believe. Children pretend to be the mother, fireman, driver, etc. by imitating actions they have witnessed others doing. As the use of dramatic play increases, they begin to use words to enhance and describe their re-enactments. Some children may even engage in fantasy, where the situations they are acting out aren’t pulled from real-life experiences.

Attention Span - Length of Time – Early ventures into the field of dramatic play may only last a few minutes, but as the children grow, develop, and experience more, they will be able to incorporate additional actions and words, which will lengthen the time they engage in such activities.

Social Skills - Interaction – Dramatic play promotes the development of social skills through interaction with others, peers or adults. As children climb the social skill ladder of development through play, they will move from pretending at the same time without any actual interaction, to pretending that involves several children playing different roles and relating to each other from the perspective of their assigned roles.

Communication – Dramatic play promotes the use of speaking and listening skills. When children take part in this type of play, they practice words they have heard others say, and realize that they must listen to what other “players” say in order to be able to respond in an appropriate fashion. It also teaches them to choose their words wisely so that others will understand exactly what it is they are trying to communicate.

Dramatic Play and Development

Dramatic play enhances child development in four major areas.

Social - Emotional – When children come together in a dramatic play experience, they have to agree on a topic (basically what “show” they will perform), negotiate roles, and cooperate to bring it all together. And by recreating some of the life experiences they actually face, they learn how to cope with any fears and worries that may accompany these experiences. Children who participate in dramatic play experiences are better able to show empathy for others because they have “tried out” being that someone else for a while. They also develop the skills they need to cooperate with their peers, learn to control their impulses, and tend to be less aggressive than children who do not engage in this type of play.

Physical – Dramatic play helps children develop both gross and fine motor skills – fire fighters climb and parents dress their babies. And when children put their materials away, they practice eye-hand coordination and visual discrimination.

Cognitive – When children are involved in make-believe play, they make use of pictures they have created in their minds to recreate past experiences, which is a form of abstract thinking. Setting a table for a meal, counting out change as a cashier, dialing a telephone, and setting the clock promote the use of math skills. By adding such things as magazines, road signs, food boxes and cans, paper and pencils to the materials included in the area, we help children develop literacy skills. When children come together in this form of play, they also learn how to share ideas, and solve problems together.

Language – In order to work together in a dramatic play situation, children learn to use language to explain what they are doing. They learn to ask and answer questions and the words they use fit whatever role they are playing. Personal vocabularies grow as they begin to use new words appropriately, and the importance of reading and writing skills in everyday life becomes apparent by their use of literacy materials that fill the area.

Dramatic play engages children in both life and learning. Its’ real value lies in the fact that it increases their understanding of the world they live in, while it works to develop personal skills that will help them meet with success throughout their lives.

Marie is the author of five books. She continues to write articles for parents and teachers.

Dramatic Play

Dramatic play permits children to fit the reality of the world into their own interests and knowledge. One of the purest forms of symbolic thought available to young children, dramatic play contributes strongly to the intellectual development of children (Piaget, 1962). Symbolic play is a necessary part of a child's language development (Edmonds, 1976).

Drama: What It Is and What It Isn't

Drama is the portrayal of life as seen from the actor's view. In early childhood, drama needs no written lines to memorize, structured behavior patterns to imitate, nor is an audience needed. Children need only a safe, interesting environment and freedom to experiment with roles, conflict, and problem solving. When provided with such an environment, children become interested in and will attend to the task at hand and develop their concentration (Way, 1967). Opportunities for dramatic play that are spontaneous, child-initiated, and open-ended are important for all young children. Because individual expression is key, children of all physical and cognitive abilities enjoy and learn from dramatic play and creative dramatics. In early childhood, the term dramatic play is most frequently used and the process is the most important part, not the production. Dramatic play expands a child's awareness of self in relation to others and the environment. Drama is not the production of plays usually done to please adults rather than children (Wagner, 1976).

Elements of Drama in the Early Childhood Classroom

Dramatic play includes role-playing, puppetry, and fantasy play. It does not require interaction with another.

Socio-dramatic play is dramatic play with the additional component of social interaction with either a peer or teacher (Mayesky, 1988; Smilansky, 1968).

Creative dramatics involves spontaneous, creative play. It is structured and incorporates the problem solving skills of planning and evaluation. Children frequently reenact a scene or a story. Planning and evaluating occurs in creative dramatics (Chambers, 1970, 1977)

Collaborative Classroom

What Is the Collaborative Classroom?

M.B. Tinzmann, B.F. Jones, T.F. Fennimore, J. Bakker, C. Fine, and J. Pierce NCREL, Oak Brook, 1990

New Learning and Thinking Curricula Require Collaboration

Collaborative Classroom - Collaboration Resources

In Guidebook 1, we explored a "new" vision of learning and suggested four characteristics of successful learners: They are knowledgeable, self-determined strategic, and empathetic thinkers. Research indicates successful learning also involves an interaction of the learner, the materials, the teacher, and the context. Applying this research, new guidelines in the major content areas stress thinking. Guidebook 2 describes these new guidelines and provides four characteristics of "a thinking curriculum" that cut across content areas. The chief characteristic of a thinking curriculum is the dual agenda of content and process for all students. Characteristics that derive from this agenda include in-depth learning; involving students in real-world, relevant tasks; engaging students in holistic tasks from kindergarten through high school; and utilizing students' prior knowledge.

Effective communication and collaboration are essential to becoming a successful learner. It is primarily through dialogue and examining different perspectives that students become knowledgeable, strategic, self-determined, and empathetic. Moreover, involving students in real-world tasks and linking new information to prior knowledge requires effective communication and collaboration among teachers, students, and others. Indeed, it is through dialogue and interaction that curriculum objectives come alive. Collaborative learning affords students enormous advantages not available from more traditional instruction because a group--whether it be the whole class or a learning group within the class--can accomplish meaningful learning and solve problems better than any individual can alone.

Classroom Management Tips

This focus on the collective knowledge and thinking of the group changes the roles of students and teachers and the way they interact in the classroom. Significantly, a groundswell of interest exists among practitioners to involve students in collaboration

in classrooms at all grade levels.

The purpose of this GuideBook is to elaborate what classroom collaboration means so that this grass-roots movement can continue to grow and flourish. We will describe characteristics of these classrooms and student and teacher roles, summarize relevant research, address some issues related to changing instruction, and give examples of a variety of teaching methods and practices that embody these characteristics. Characteristics of a Collaborative Classroom

Collaborative classrooms seem to have four general characteristics. The first two capture changing relationships between teachers and students. The third characterizes teachers' new approaches to instruction. The fourth addresses the composition of a collaborative classroom.

1. Shared knowledge among teachers and students

In traditional classrooms, the dominant metaphor for teaching is the teacher as information giver; knowledge flows only one way from teacher to student. In contrast, the metaphor for collaborative classrooms is shared knowledge. The teacher has vital knowledge about content, skills, and instruction, and still provides that information to students. However, collaborative teachers also value and build upon the knowledge, personal experiences, language, strategies, and culture that students bring to the

learning situation.

Consider a lesson on insect-eating plants, for example. Few students, and perhaps few teachers, are likely to have direct knowledge about such plants. Thus, when those students who do have relevant experiences are given an opportunity to share them, the whole class is enriched. Moreover, when students see that their experiences and knowledge are valued, they are motivated to listen and learn in new ways, and they are more likely to make important connections between their own learning and "school" learning. They become empowered. This same phenomenon occurs when the knowledge parents and other community members have is valued and used within the school.

Additionally, complex thinking about difficult problems, such as world hunger, begs for multiple ideas about causes, implications, and potential solutions. In fact, nearly all of the new curricular goals are of this nature--for example, mathematical problem-solving--as are new requirements to teach topics such as AIDS. They require multiple ways to represent and solve problems and many perspectives on issues.

2. Shared authority among teachers and students

In collaborative classrooms, teachers share authority with students in very specific ways. In most traditional classrooms, the teacher is largely, if not exclusively, responsible for setting goals, designing learning tasks, and assessing what is learned.

Collaborative teachers differ in that they invite students to set specific goals within the framework of what is being taught, provide options for activities and assignments that capture different student interests and goals, and encourage students to assess what

they learn. Collaborative teachers encourage students' use of their own knowledge, ensure that students share their knowledge and their learning strategies, treat each other respectfully, and focus on high levels of understanding. They help students listen to diverse opinions, support knowledge claims with evidence, engage in critical and creative thinking, and participate in open and meaningful dialogue.

Suppose, for example, the students have just read a chapter on colonial America and are required to prepare a product on the topic. While a more traditional teacher might ask all students to write a ten-page essay, the collaborative teacher might ask students to define the product themselves. Some could plan a videotape; some could dramatize events in colonial America; others could investigate original sources that support or do not support the textbook chapter and draw comparisons among them; and some could write a ten-page paper. The point here is twofold: (1) students have opportunities to ask and investigate questions of personal interest, and (2) they have a voice in the decision-making process. These opportunities are essential for both self-regulated learning and motivation.

3. Teachers as mediators

As knowledge and authority are shared among teachers and students, the role of the teacher increasingly emphasizes mediated learning. Successful mediation helps students connect new information to their experiences and to learning in other areas, helps

students figure out what to do when they are stumped, and helps them learn how to learn. Above all, the teacher as mediator adjusts the level of information and support so as to maximize the ability to take responsibility for learning. This characteristic of collaborative classrooms is so important, we devote a whole section to it below.

4. Heterogeneous groupings of students

The perspectives, experiences, and backgrounds of all students are important for enriching learning in the classroom. As learning beyond the classroom increasingly requires understanding diverse perspectives, it is essential to provide students opportunities to do this in multiple contexts in schools. In collaborative classrooms where students are engaged in a thinking curriculum, everyone learns from everyone else, and no student is deprived of this opportunity for making contributions and appreciating the contributions of others.